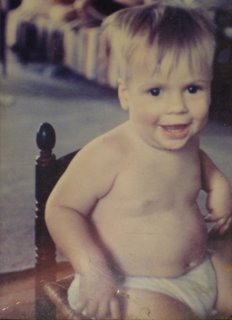

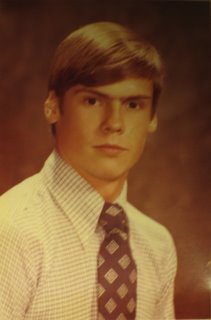

Brothers and Sisters: Winston Deaver (12/5 1959 - 11/23 1991)

by Charlotte Deaver

My brother was handsome: square-jawed, tall, intense, sensitive, fierce. But most of the time my siblings and I avoided him because we always expected he was going to either say something mean or annoying, or just punch the shit out of us.

At the age he was in this picture above (18), he wasn't punching me anymore. He took his rage and frustration out on my younger brother, other fucked up kids, and himself, but not his little sister. We smoked pot together and listened to a lot of the same music. He was nice to my friends, a few of whom we even had in common. We were seniors in high school at the same time, Winston having stayed back a year to graduate. Because I had missed the submission deadline, his graduation picture appears in our senior yearbook and mine doesn't. I used to regret that I'm not in my high school yearbook, but now I like to think of Winston's photograph there, representing us.

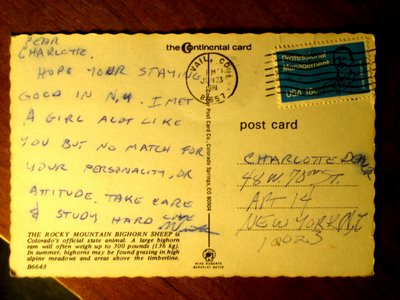

I found this postcard recently and realized that I am not crazy for remembering, along with the difficult stuff, the sweetness of my brother. He loved me. He cared about me. He even met a girl he compared to me. For our family, as childhood brothers and sisters, this kind of tenderness was rare.